Last year I met someone who I very quickly fell in love with. No, it’s not Thomas Straker. But I only met her because she was supposed to dine at his restaurant but changed her mind last minute because she hated his videos and decided to go to my restaurant instead. It was a Saturday, a night of the week I seldom work, and I was her server.

What proceeded was a 3-month romance, then a breakup. I was heartbroken. What an absolute horrible year 2025 had been, and by December 24th I found myself single, sad, worried about my restaurant’s future, and lonely.

I felt sorry for myself for a whole 48 hours. Literally, that was all. 2 whole days of wallowing. And then something beautiful happened; nothing happened at all.

Nothing changed. At least not materially or tangibly. I was still alone in my flat with my pet puppy Yossarian. It was Boxing Day. Christmas went relatively well with all my family and gifts were exchanged, and my kids were flooded with presents and attention. My dad cooked a beautiful meal. I saw my siblings and their partners, and it was genuinely a joyous time. But inside, I was hurting. Keeping shit together, but ultimately just crestfallen.

The festive period often evokes the strongest feelings of desolation and isolation. It magnifies the sense of melancholy because everywhere around is a forced, commercial-led “joy” we are pressured to embrace. If you’re not in a good place mentally, it only accentuates the polar opposite feeling of the external-world’s intentions.

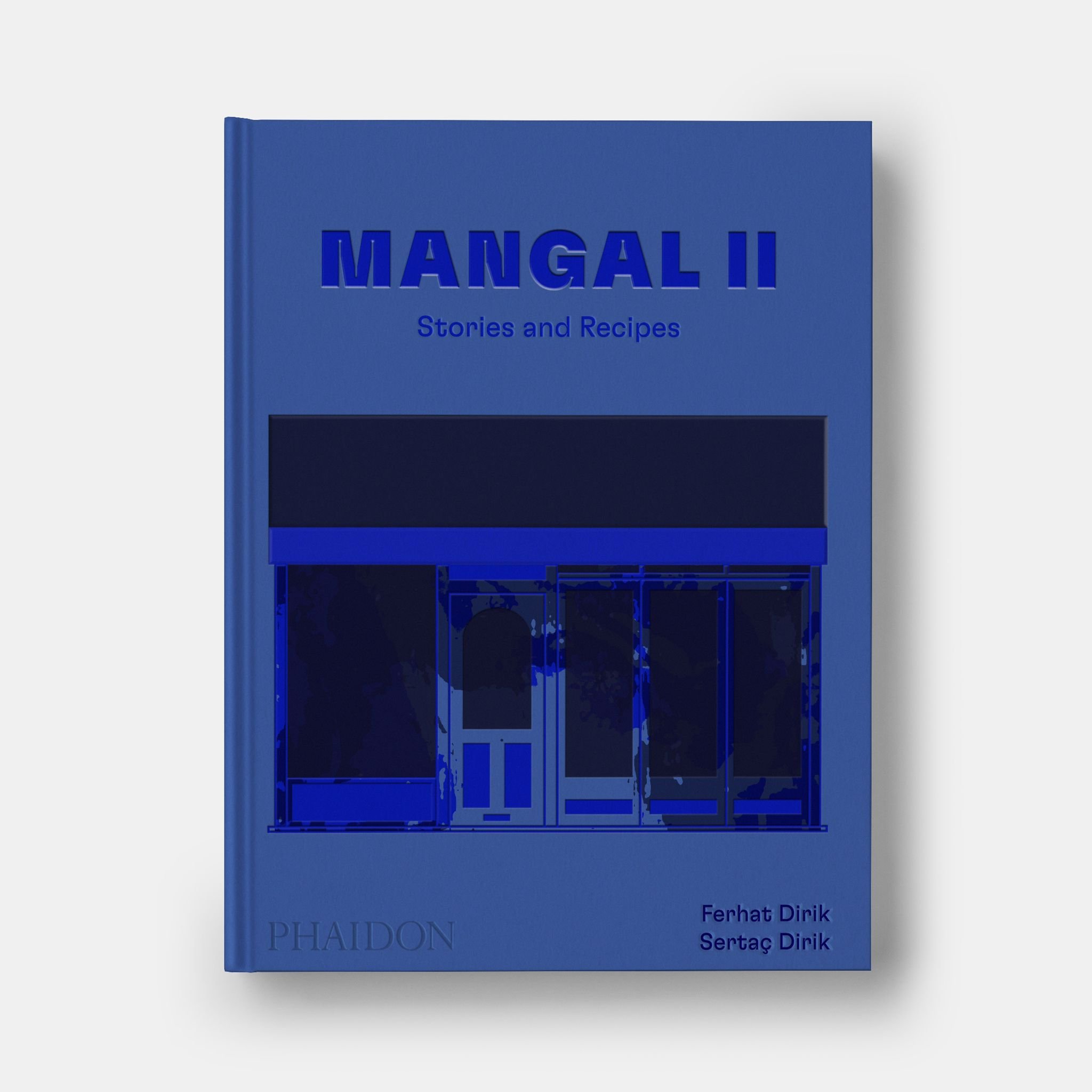

I must state that I am fully aware this is a restaurant newsletter and not my very own Carrie Bradshaw journal. A sad Ferhat is an unproductive Ferhat, and an unproductive Ferhat unfortunately seeps into an underperforming Mangal II. Look, I don’t make the rules, that’s just the way it goes. And an unproductive Mangal II risks closure, that’s the long and short of it.

But on Boxing Day 2025, I woke up and something just clicked. Nothing actually changed, as I said, but that day something shifted. I took a long hard look at my life, at the year I’d had, and weighed up why things weren’t necessarily working, personally and professionally. And then the perceptive switch-up happened and it hit me like a wall - a wall made up of pillows, soft, and comforting, and full of a dreamy sense of love and appreciation. I began to really embrace what I already had. My own flat. My beautiful and vibrant children, and their infectious positivity and personalities. My adorable dog, and our morning walks in the forest, secluded from the daily rigours of work and socialising. A 90-minute refuge where he’d scamper in the mud and I’d fill my lungs with nature’s beauty, surrounded by a free-flowing river and fellow nice local dogwalkers who I’ll chitchat with. I began to appreciate my very good friends who care about me, who check in on me and want to see me. And then there’s my parents and siblings who see me for who I am and still have room in their hearts to love me unconditionally.

I looked at my restaurant.

It survived. It pulled through 2025, debts and all. It was still standing and still fighting. So many restaurants were forced to close last year, a lot of local favourites. And knowing that we were on the brink of joining that pitiful list brought me no pleasure. Remaining alive felt bittersweet amongst a sea of contemporaries who could not afford that luxury. A bit like going to war and remaining one the last ones standing at the end. You celebrate victory but mourn the dead. Glory and loss going hand-in-hand.

From that day forth, for a good month, I became deliriously happy. A new sense of fulfilment filled me where I became very zen-like, truly thankful for each day and all that I had already. I began to love my life in a stupor-state of a feverish consciousness. Every morning felt like a gift. Every sip of coffee life-affirming. Every exchange with a friend all-encompassing. Every shift at work like a family reunion without the drama, like a summer cookout with free-flowing conversations, laughter, and a togetherness. I was happy. Maybe the happiest I ever felt in my adult life, from what I can recall.

I’ve run with that energy and mindset since. Today, that over-the-top ecstasy has plateaued a little to reach a point of contentment and a general positivity that feels sustainable and realistic. A sad day may come up in the near future, but I feel much more equipped to deal with it now having a backdrop of a newer sense of perspective to how fortunate I am in life, and how good things are in relation to the other ills this world has to offer.

I finally feel comfortable in my own skin. I finally feel at peace. And Mangal II will reap all its benefits.

We hit 2026 with an absolute bang: A Turkish-Ocakbașı fuelled Sunday Roast which has bookings seismically shaken and spiked. We’re busy, and were pretty damn full by the end of January (often the worst month for hospitality). We have a new lunch menu offering in the works, tonnes of new dishes on our à la carte which are truly delicious and fit in with our Anatolian root-British garnish ethos. There are very exciting pop-ups soon to be announced, and a work field trip to Istanbul next month. Customer feedback has almost exclusively been overwhelmingly positive. We’ve priced things fairly, in a mostly affordable sense to make dining out a realistic aim for the public in East London. Most of all, and I cannot stress this enough, I really love my team here at Mangal II. We had a staff party in early January and to witness how close everyone was, with even past staff members joining because we’re all one big family here, was so endearing to witness. We all ate pizza, played pool, and went to the pub, and no one wanted the night to end.

I love going to work now. I feel a happiness and comraderie I hadn’t felt in ages. It was my birthday a few weeks ago and so many people personally sent me messages to wish me well, not least most of my staff. It meant the world to me. In a stupid moment of hubris, I started counting the sheer volume whilst on holiday in Rome. After the number 86, 86 separate individuals taking time out of their day to celebrate my birthday in some form or another, I stopped counting, a little embarrassed at this act of mine. But it reinforced this: I am loved. I have good friends. I have amazing staff. I have a beautiful restaurant that I want to keep going and protecting and harnessing. I feel a duty to keep Mangal II going for as long as possible, because I love my customers and every time one leaves my home happy and full, I receive an endorphin rush.

Life feels good. Mangal II feels hopeful. And 2026 feels like a new beginning. We move. And whilst Thomas Straker played a very minor part in this revival, in a roundabout way his annoying face was the catalyst for all these changes. I’ll make sure I’ll buy a cube of his branded-butter the next time I stumble into Waitrose.